The Mahaska Legacy: How a Native Peacemaker and a Union Gunboat Carried One Name into History

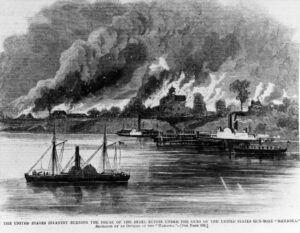

Engraving from Harper’s Weekly (1862) depicting U.S. infantry setting fire to the Virginia estate of Confederate secessionist Edmund Ruffin, under the protective guns of the USS Mahaska. The Union sidewheel gunboat, shown in the foreground, patrolled the James River during early Civil War campaigns. The image, sketched by an officer aboard the Mahaska, captures the intensity of riverine warfare and symbolizes the Union’s campaign to dismantle the ideological and physical strongholds of rebellion.

OSKALOOSA, Iowa — It’s easy to forget what a name carries. For most of us, Mahaska is the county on our driver’s license, the statue at the courthouse square, the word that sits atop signs and letterheads. But long before it was a place, Mahaska was a man — and not just any man. He was a warrior turned peacemaker, a tribal leader who walked away from bloodshed in pursuit of stability for his people. And in 1861, at the dawn of America’s bloodiest war, that name took to the water aboard a steam-powered Union warship.

The story of the USS Mahaska is not just a Civil War footnote. It’s a reflection of what this county was built on: courage, resilience, principle, and the painful complexity of living between two worlds.

Chief Mahaska: The Man Before the County

Born around 1784 in what is now southeastern Iowa, Mahaska, known to his people as Maxúshga or “White Cloud,” became chief of the Ioway Nation at a time when the land now called Mahaska County was home not to farmsteads or brick storefronts, but to forests, prairies, and ancient tribal trails. His father, also a chief, had been murdered by a rival tribe, and Mahaska responded with vengeance. It’s said he killed at least eighteen in battle before he was even twenty-five.

But Mahaska’s story didn’t stop at the edge of a blade. After a brief imprisonment by the U.S. government and a narrow escape from retribution by enemies, Mahaska changed. He put down his weapons, built a cabin, adopted a western shirt and trousers, and began farming. At a time when many tribal leaders urged resistance to white encroachment, Mahaska chose another route — one of cooperation, however uneasy.

That decision cost him the full support of his own people, some of whom viewed him as too accommodating. Still, Mahaska held firm. When his tribesmen sought revenge on the Omaha, he intervened to stop them. In the end, he was killed by those very warriors in 1834. But his name — and what it stood for — survived.

In 1843, Iowa lawmakers honored him by naming a new county, Mahaska. And in 1909, a bronze statue of the man was unveiled on Oskaloosa’s square. He stands there still, facing west, stone-eyed and silent, watching over the land that bears his name.

USS Mahaska: A Gunboat Named for Peace in a Nation at War

Eighteen years after the county’s founding, as the United States tore itself apart over slavery and sovereignty, the U.S. Navy launched a wooden, sidewheel steamer gunboat from the Portsmouth Navy Yard in Maine. She was 1,070 tons, 228 feet long, and armed with Dahlgren cannons and a 100-pounder Parrott rifle. Her name: USS Mahaska.

It’s worth pausing on that. In the same year that Union troops first marched to war in defense of the Constitution, the Navy chose to name a warship not after a politician or a city, but after a Native American chief from a place few in Washington had ever been.

Under the command of 25-year-old Lieutenant Norman H. Farquhar, who would later rise to admiral, the USS Mahaska was commissioned on May 5, 1862, and sent south. She was designed as a “double-ender,” with rudders and propulsion at both ends — perfect for the tight, treacherous rivers of Virginia and the Carolinas.

The Fire of War: Mahaska Under Cannon and Ink

In the summer of 1862, just weeks after she joined the fleet, the Mahaska was shelling Confederate batteries on the Appomattox River, clearing the way for Union troops. On July 1, she supported operations at Harrison’s Landing, during the retreat of Union General George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac after the failed Peninsula Campaign.

The Mahaska’s cannons roared from the James River as the army dug in. The engagement was so dramatic that it was captured in a Harper’s Weekly engraving — a woodcut image based on a sketch made aboard ship. It showed U.S. infantry burning the home of Edmund Ruffin, the virulent secessionist credited with firing the first shot at Fort Sumter, under the protective guns of the Mahaska.

That image didn’t just show a moment of war. It showed a ship bearing the name of a Native peacemaker, unleashing fire on the ideological architects of disunion. There is something deeply ironic, and deeply American, about that scene.

Later that year, the Mahaska destroyed Confederate earthworks at West Point, Virginia, captured enemy schooners, and patrolled the Chesapeake. She moved south in 1863, joining the blockade off Charleston, bombarding Fort Wagner, Morris Island, and Fort Sumter — the same fort whose fall had ignited the war.

In 1864, she was assigned to Florida, assisting in the expedition to Jacksonville, patrolling the St. Johns River, and capturing Confederate vessels until the war’s final months.

Fading From View: Decommissioning and Civilian Life

After the war, the Mahaska remained in service patrolling Southern waters. She was finally decommissioned in New Orleans on September 12, 1868, and sold to a Boston merchant named John Dole. Her final name in civilian service was Jeannette, but no records survive detailing her last days.

Like many warships of the Civil War, she likely ended up dismantled — stripped of her fittings, her wood sold off, her memory slowly receding into history.

Why This Story Matters to Mahaska County

It’s not just a ship. It’s not just a statue. It’s a name — and a reminder. When we say “Mahaska,” we are invoking both a man who sought peace amid chaos and a ship that fought for unity amid disunion. It’s a heritage built not on power alone, but on principle.

Chief Mahaska, the man, tried to forge a future between cultures — a road of compromise, survival, and dignity. The USS Mahaska, the ship, carried that name into the storm, through cannon fire and history’s eye.

Mahaska County isn’t just a name on a map. It’s a story of two legacies bound by one word.

So the next time you pass the statue in the square, or see the county name on a courthouse document, remember: that name once echoed off Virginia’s rivers, roared through Charleston’s blockade, and rang out in the pages of Harper’s Weekly. It’s the story of a chief. A warship. A county. And a legacy still very much alive.

Editor’s Note: Oskaloosa News welcomes contributions from descendants of Chief Mahaska, Civil War researchers, and local historians. If you have artifacts, family stories, or historical documents related to this story, we encourage you to reach out. Together, let’s preserve and honor what this name truly means.