Mental Health Care Away From Home Can Be Difficult For College Students

By Lily Bohlke May 16, 2019

When Mary Rose Bernal sought help for her eating disorder during her first year of college in Iowa, she said she felt like she had to educate her Iowa providers “who should have known better.”

Bernal, 21, originally from San Jose, California, and a spring 2019 graduate of Grinnell College, has struggled with an eating disorder since she was 15. When she was 16 and living in San Jose, she acquired a support team consisting of an eating disorder specialist, who worked out of an eating disorder clinic, a nutritionist and a therapist.

“When I first came to Grinnell, I think I had none of that,” Bernal, who became a member of Grinnell’s National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) chapter, said about her support team back home.

Beginning and attending college or graduate school can be a major life transition for many students. It especially becomes difficult, however, for students with mental illness who move away from home and care designed to deal with their specific health care problem.

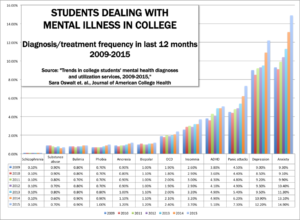

One of every three U.S. college students shows symptoms of a mental health problem such as depression, generalized anxiety disorder or being suicidal, a study by Sara Oswalt, of the University of Texas at San Antonio, and other researcher said in a 2018 report, “Trends in college students’ mental health diagnoses and utilization of services, 2009-2015.” Depression and anxiety are the two most common mental illnesses among college students, anxiety having surpassed depression, affecting between 38 and 55 percent of college students, the study, published in the Journal of American College Health, showed.

Common mental health concerns include anxiety, depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, stress, sleep difficulties and bipolar disorder, among others. These concerns can add to the pressures students already may be under, trying to do “well academically, getting a good job and paying off educational loans,” Brenda Lovstuen, director of counseling at Cornell College’s Counseling Center, said.

Lovstuen said counselors in Mount Vernon, where Cornell exists, fill their schedules regularly, so sometimes students who opt not to use the college’s Counseling Center have to travel to the Iowa City or Cedar Rapids areas.

However, limited resources, especially preventative ones, exist in Iowa for people with eating disorders, said Marcy Shrum, a social worker and vice president of the board of the Eating Disorder Coalition of Iowa.

“We get calls from all kinds of people who are looking for resources,” Shrum said. “I mean, I think the most unfortunate part for us is when we don’t really have resources to offer them.”

While therapists treating eating disorders are in Iowa, the state’s only inpatient treatment option is at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Iowa City, however, is in east-central Iowa, leaving people in central and western Iowa either driving a long distance for inpatient care or passing on treatment.

The stress in college extends into graduate school, including in high-pressure fields. “Very similarly to undergrads, we all have pressure to do well in school and to get good grades and do all the extra things so we can eventually get a job,” Nicole Nitschke, 24, a student at the University of Iowa’s College of Medicine and co-president of the college’s NAMI chapter, said.

Yet, barriers can exist when the students try to seek the mental health care they may want or need, interviews revealed. These barriers can take a variety of forms, such as limited statewide access to care, limited college resources or stigmas surrounding mental illness.

Differences also can exist in the accessibility of care depending on how close students are to specific resources for dealing with their illness.

STRUGGLES AWAY FROM HOME

Bernal said the lack of professionals near her who specialize in eating disorders has affected her ability to receive care she needs. When she began college at Grinnell, her main support system was through the college’s Student Health and Wellness office.

She stayed in touch with her specialist back home, though. She would see a nurse at the college’s health and wellness office on a regular basis, and if vital signs such as pulse, blood pressure, and weight fell below a certain point, her specialist in California instructed her to be hospitalized.

In December 2015, just a few weeks before the end of the fall semester, Bernal’s vitals dropped below the point established by her specialist. While the nurse she was seeing at the college had told Bernal that the nurse did not have a lot of experience with eating disorders, Bernal said she thought that would be fine.

Bernal ended up going to Grinnell Regional Medical Center, then University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. “They drove me at night, in an ambulance. I was reading my Shakespeare at the time for homework because I was in denial. I was like, okay, I’m going to go back to school tomorrow or the day after.”

Bernal stayed at U of I Hospitals for two or three days — she couldn’t recall which — but she said nobody seemed to be familiar with her condition. She eventually talked to a cardiologist, “who was like, ‘yeah, I’ve seen eating disorders before and this doesn’t look like you’re in a good spot,’” Bernal said. “Because I felt like I was, up to that point, educating everyone.”

When she left the hospital in Iowa City, she went back to Grinnell and finished the semester. But when she went back to San Jose for winter break, she was hospitalized again. She had a much different experience there, staying first at Stanford Children’s Health, and then a residential program at Cielo House, an eating disorder treatment center where she stayed for a little less than three months.

She was in an outpatient program for a while after that. And, she was angry at Grinnell College and the health care people she had seen in Iowa.

“I had to leave school, I had to take an entire semester off, whereas if that kind of stuff had been remotely in place here, I would not have had to do that.” she said. “And I didn’t know what they were doing with me, and they could have caught it a lot faster.”

Related: Mental Health Issues Growing Among Iowa High School Students

Legislation like the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act requires mental health to be treated at the same level as physical health. Shrum, of the Eating Disorder Coalition of Iowa, said prevention and long-term recovery options in Iowa still are limited.

“One of the things that I think is a barrier is the level of care requirements that you have to meet,” Shrum said. “I mean, we’re telling people you need to be more sick before you can have inpatient treatment. And so people have to get sicker before they need that, which we know is kind of adverse because we want to catch it sooner than later, before it gets to a point that they need inpatient care.

“But even if you could have specialized care at the beginning and nutrition therapy at the beginning, those things, I think, would make a big difference.”

WORKING WITH THE SUPPORT SYSTEM

Declan Jones, 20, originally from Chicago, Illinois, and attending Grinnell College, said he went to the college’s health and wellness office for an appointment midway through the spring 2019 semester for help dealing with his stress and anxiety. At the end of the appointment, however, he was told the office could not see him on a regular basis, he said.

He said the person he met with at the office pointed him toward either group therapy or a 24/7 counseling hotline. However, Jones said he did not feel like either option met his needs; he opted to talk to friends and family instead. “There are certain things that I filter from each of those groups,” Jones said.

“Seeing as they’re at capacity,” he said about the college’s health and wellness office, “I would have some self-resentment if I took up some of that resource pool if I’m not in crisis, which I get the impression now that you need to be in order to receive therapy.”

The health and wellness office has between 4.0 and 5.0 full-time equivalency staffing hours during weekdays. Multiple providers who also practice in the town of Grinnell support college students as well as others in town. The health and wellness office has a mental health registered nurse who helps students coordinate any appointments with outside care, a team from the wellness office consisting of director of health services Deborah Shill, counselor Paul Valencic and doctoral program coordinator Charles Cunningham wrote in an email to IowaWatch.

Eric Wood, Grinnell’s dean of wellness until the end of April, said in an interview available counseling depends on the time of year.

For example, in mid-March, the college’s wellness office was hearing that community providers’ schedules were getting full, Wood said. “This is a significant challenge for the community as well as the college,” he said.

Even when mental health care resources are available, the stigma around mental illness can play a role in preventing students from getting the care they need. For many students, college is their first time living independently.

Thomas Zigo, staff counselor at Grinnell’s health and wellness office, started a men’s group to be able to come together and be emotionally vulnerable in a space meant to challenge “traditional ideas of hegemonic masculinity,” which, he said, often are passed down to generations through family, friends and the media.

“Unfortunately, many men are conditioned at a young age to be stoic and emotionless. It seems that toxic masculinity gender roles are passed down from generation to generation; learned at an early age and reinforced throughout life,” Zigo said.

Zigo’s men’s group is just one of the ways in which Grinnell College has been working to expand its mental health resources. Some initiatives the college’s health and wellness office has been working on include developing drop-in counseling services for students, implementing the 24/7 counseling hotline that Jones was referred to and formalizing a crisis response system for when students encounter mental health emergencies.

Related: Mental Illness Emerges As The Most Common Hidden Disease On College Campuses

Men’s issues are not the only sources of the stigma around mental illness, however. Barry Schreier, the University of Iowa’s director of University Counseling Services, said his office works to provide multicultural awareness, recognizing that the mental health care model of having sit-down therapy sessions does not work for everyone. The U of I also has multilingual counselors.

“For some folks from certain cultures, the perception is: going to see a mental health professional means that you are, and I’ll use this language because I’ve heard it from some of our international students, it means that you’re crazy. ‘And I’m not crazy. I’m just having a concern I need to talk to someone about,’” Schreier said.

University Counseling Services counselors try to alleviate this stigma as best they can by providing drop-in anonymous counseling, sometimes referred to as advice giving, problem solving or coaching.

The service’s counseling staff has almost doubled in the last four years, and the counseling service saw more students in the 2018-19 school year by March 1 than it did during all of the previous year. So despite the fact that the center grew, wait times did not get shorter, Schreier said.

“If we expand the service, students will fill it,” he said. “We’re seeing a lot more students but we’re still at capacity.”

Part of the reason that mental health providers in Grinnell and Mount Vernon are limited is their locations. Zigo said resources in Grinnell are more limited than where he previously worked in Athens, Ohio, where the University of Ohio exists, in part because Grinnell is a rural Iowa town. The U of I, in Iowa City and with a specialty hospital, has additional resources that some of the schools in smaller towns do not have.

Nitschke, the medical student, said that within the medical community, people talk about how there is a shortage of psychologists and psychiatrists in the country, which can make it more difficult for people to connect with the mental health resources they may need.

“Being in medical school, we’re associated with a hospital, but I think any undergraduate or graduate institution that doesn’t necessarily have one close by, definitely would probably have a harder time getting these resources,” Nitschke said.

This story was produced by the Iowa Center for Public Affairs

Journalism-IowaWatch, a non-profit, online news website that collaborates

with news organizations to produce explanatory and investigative

reporting. Read more at www.IowaWatch.org.